Transitions

The Future of Work in the UK in the Age of AI

AI and automation are reshaping industries across the UK, driving significant changes in the labour market. This report explores the opportunities these technologies present for growth and productivity, while also addressing the risks they pose to workers' wellbeing and job security. We assess the broader impacts of AI on the future of work and how these changes will shape the UK's economic landscape.

A report by Oliver Nash, Anna Thomas, Abby Gilbert, Kester Brewin, and Sir Christopher Pissarides as part of the Pissarides Review into the Future of Work and Wellbeing, hosted by the Institute for the Future of Work (IFOW)

October 2024Setting the Scene

Automation technologies, particularly robotics and artificial intelligence, are bringing significant changes to labor markets. How are workers in the UK affected? What is the impact on productivity and growth? Can the situation be improved, and if so, how?

While improving productivity is essential, the wellbeing of workers should also be a key objective. Higher productivity helps governments achieve social goals like healthcare and education, but if work leads to unhappiness and mental health issues, is that a price worth paying?

Policymakers often focus too much on GDP growth. Measuring GDP precisely is fraught with difficulties, and small differences should not drive major economic decisions. Wellbeing is increasingly recognized as an important factor in evaluating policies.

Here are some facts to set the scene about the state of the UK's productivity and workforce development:

- Productivity gap: The UK has one of the lowest productivity rates among G7 countries. As of 2023, output per hour worked remains significantly lower than in the United States, Germany, and France.

- Stagnant productivity growth: Since the 2008 financial crisis, UK productivity growth has averaged around 0.3% per year, compared to the pre-crisis average of 2% per year. British productivity would be 25% higher today if it had continued growing at the 1979–2008 trend rate.

- Decline in Job Training: The percentage of UK workers receiving job-related training has declined from 15% in the mid-1990s to about 9% in recent years, impacting skill development and productivity.

- Apprenticeship Starts Decrease: Apprenticeship starts in England have fallen by over 25% since the introduction of the Apprenticeship Levy in 2017, despite government efforts to boost vocational training.

- Low Investment in Adult Skills: The UK invests less in adult skills training compared to other OECD countries, leading to a significant skills gap in key sectors like manufacturing and technology.

- Digital Skills Shortage: Digital skills shortages are estimated to cost the UK economy over £63 billion annually, as businesses struggle to find qualified workers in IT and technology roles.

- Lag in AI Adoption: Only about 15% of UK businesses have adopted AI technologies, lagging behind countries like France (21%) and Germany (23%), potentially impacting competitiveness.

- Technical Skills Shortage: The UK ranks low among OECD countries for intermediate technical skills, highlighting a gap in vocational education and training.

- Regional Productivity Disparities: Productivity per worker in London is over 50% higher than in some other UK regions, indicating significant regional disparities.

- Gender Pay Gap Persists: As of 2023, women in the UK earn on average 14% less than men, impacting overall economic productivity and equality.

Exploring the UK's Good Work system

At the heart of creating a thriving economy and equitable society is the concept of Good Work. This system brings together various actors, including policymakers, businesses, academic institutions, and workers' rights organisations, to promote job quality, wellbeing, and economic inclusion.

This interconnected system requires collaboration across different sectors and regions. As highlighted by the Institute for the Future of Work, one of the missing pieces in the conversation is thinking about transitions within systems, geographies, firms, and roles (Thomas and Nash, 2024). The key is focusing on multiple levels, integrating multidisciplinary approaches, and ensuring that transitions lead to sustainable, forward-looking outcomes for everyone.

The following interactive system map illustrates how these different actors and factors are connected. It highlights how innovation policies, skills development, and workplace wellbeing are interdependent. As you explore, consider how different elements interact to support good work, and how action at one level (such as national policy) can influence outcomes at other levels (such as regional development or workplace wellbeing).

This system map visualises the key actors and interactions driving the UK’s Good Work system, exploring relationships between innovation policies, workplace rights, and job creation.

Understanding the UK’s Innovation Ecosystem

The UK’s innovation ecosystem is a complex, interconnected structure that drives technological advancement, economic growth, and societal wellbeing. This ecosystem involves various stakeholders, from government bodies and private sector players to academic institutions and regional authorities.

Investments in R&D, adoption of new technologies, and fostering collaborative environments between public and private sectors are crucial for maintaining the UK's competitive edge in the global market.

The visualisation below illustrates the various components of this ecosystem, highlighting the scale of investment, innovation, and collaboration across different sectors, regions, and stakeholders. You can interact with the bubbles to explore different areas of focus, including funding sources, sectoral innovation, and geographical disparities.

The context: Economic stagnation, slow produtivity growth and growing regional disparities

The United Kingdom is facing a period of economic stagnation, with real wage growth stagnant over the past 16 years. Average weekly wages have barely improved since their peak in 2008, and for many workers, real wages are lower than they were a decade ago. This reflects not only global trends but also specific domestic issues related to work and productivity.

This report identifies four key barriers that contribute to the UK’s economic challenges:

- Underinvestment in workforce development: There has been insufficient focus on equipping workers with the skills needed for a rapidly changing job market, limiting productivity growth.

- Barriers to technological adoption: Institutional, cultural and infrastructural hurdles have slowed the uptake of new technologies that could enhance productivity across industries.

- System bottlenecks and inefficiencies: The functioning of key systems, including skills provision and regional innovation ecosystems, are hindered by significant innovation bottlenecks that impact system functioning, limit collective intelligence, constrain growth and preventing optimal collaboration.

- Regional disparities in economic opportunities: Significant gaps in investment and access to quality work across different regions have deepened economic stagnation and reduced overall productivity.

Fig 1: GDP per hour worked in the UK, compared to historical productivity trends.

The majority of subregions with productivity above the UK average are located either in London or in the South East

Figure 5 shows labour productivity for all 179 ITL3 subregions in the United Kingdom, grouped by ITL1 countries and regions in 2022.

There were 23 ITL 3 regions with labour productivity more than 20% below the UK average. The lowest productivity was in Powys in Wales.

There were 23 ITL 3 regions with labour productivity more than 20% below the UK average. The lowest productivity was in Powys in Wales.

Fig 1: GDP per hour worked in the UK, compared to historical productivity trends.

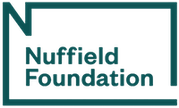

Firms with above average productivity (outside the top ten) have contributed to the slow down in productivity in the UK

Nevertheless, the productivity growth contribution from UK firms for the non-financial business economy in the top decile of the distribution of firms’ (level of) productivity is very strong, according to firm-level data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). It has not shown any sign of dropping off and is now contributing the bulk of current productivity growth.

In contrast, firms with above-median productivity levels (in the sixth to ninth decile of the distribution) have accounted for the lion’s share of the productivity slowdown in the non-financial business economy since the global financial crisis.

These firms, which have the potential to be productive, have not benefited from the diffusion of technology and innovation from the most productive companies. This has been exacerbated by stagnant foreign trade, changing patterns in foreign direct investment (Driffield et al, 2023) and the UK’s lack of deeper integration in global supply chains.

Fig 3: Contribution of firms with different worker productivity levels to change in average productivity growth, non-financial business economy, 1998-2019, percentage.

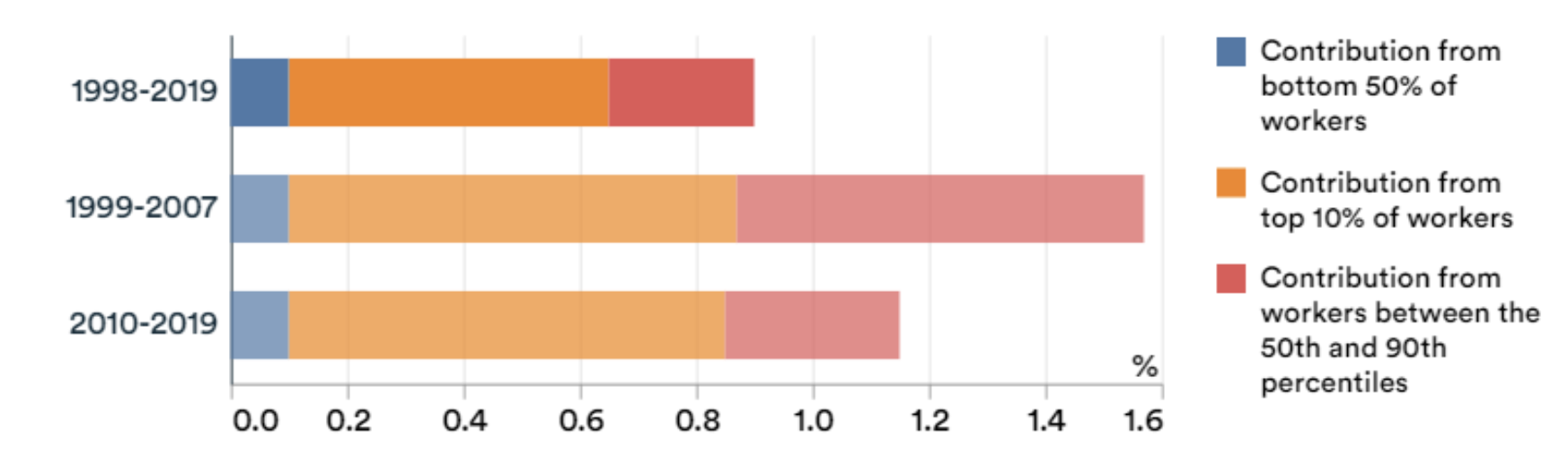

With its productivity growth slowing for the past 15 years in the UK, additional working hours have been contributing more to GDP growth than better productivity

The challenge for the next decade is daunting because of slower population and labour force growth.

Except in the unlikely scenario of a sharp increase in immigration, productivity growth will need to accelerate. Indeed, if the current trend in productivity growth were to continue for the next two decades, it will not be possible to sustain current living standards, let alone deliver sustainability and improved well-being.

For instance, even doubling the current productivity growth rate (from 0.5% to 1% a year) over the next 12 years will only be sufficient to achieve the same rate of GDP growth as in the past decade

Fig 3: GDP Growth Decomposed into Total Hours and Labour Productivity, United Kingdom, annual %, 1996-2035

At the heart of this problem are the UK’s twin second cities: Greater Manchester and Birmingham.

With populations of around 2.8 million each, their size means they must be centre stage not just for the sake of their own prosperity, but also for the sake of Britain’s. They are too big to fail.

Closing their productivity gaps with London to those that Lyon and Toulouse have with Paris would narrow the UK’s output gap to Germany by a fifth.

But honesty about the scale of change required is essential. It would require increasing each city’s business capital stock by 15 to 20 per cent; over 160,000 additional high-skilled workers in each city; city centres expanding up or out; and billions of central government investment to expand transport networks.

Fig 1: GDP per capita across city regions in the OECD

Source: OECD regional accounts data; The FT, John Burn-Murdoch (2023) - Is Britain really as poor as Mississippi?

Business R&D growth in the UK has been concentred within a few regions, with others lagging significantly or going backwards

The United Kingdom is currently experiencing economic stagnation, with real wage growth remaining flat over the past 16 years. Average weekly wages have barely increased since their peak in 2008, and for many workers, real wages are now lower than they were over a decade ago. This stagnation reflects not only global economic trends but also domestic challenges related to work and productivity.

This report posits that one of the key factors contributing to Britain's economic stagnation is the underinvestment in workforce development and barriers to technological adoption. By restricting essential investments in skills training, innovation, and digital infrastructure, the UK has hindered its ability to embrace new technologies that could enhance productivity and create good work opportunities. Addressing these barriers is crucial to revitalising the UK economy and ensuring that technological transformation benefits workers across all regions.

Fig 1: GDP per hour worked in the UK, compared to historical productivity trends.

Skills Development: UK Level 3 Qualifications

In the United Kingdom, nearly a third of young people do not reach Level 3 qualifications by the age of 18—compared to just one in five in countries such as France and Germany. This gap in skills development is a critical factor contributing to the UK’s economic stagnation and declining productivity.

Level 3 qualifications, including A-levels and vocational equivalents, are essential in equipping workers with the skills needed for the modern labour market. However, underinvestment in education and workforce training has led to significant disparities in qualification levels across different regions of the UK, limiting opportunities for young people and slowing the country’s economic growth.

This interactive map from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) highlights the percentage of the population with Level 3 or above qualifications across various regions in Great Britain. Understanding these regional disparities is key to addressing the broader issues of skills development and workforce readiness.

Fig 1: Percentage of population with Level 3 or above qualifications by region in Great Britain (ONS, 2021).

Almost a third of young people are not undertaking any education by age 18 – compared to just one in five in France and Germany

The United Kingdom is currently experiencing economic stagnation, with real wage growth remaining flat over the past 16 years. Average weekly wages have barely increased since their peak in 2008, and for many workers, real wages are now lower than they were over a decade ago. This stagnation reflects not only global economic trends but also domestic challenges related to work and productivity.

This report posits that one of the key factors contributing to Britain's economic stagnation is the underinvestment in workforce development and barriers to technological adoption. By restricting essential investments in skills training, innovation, and digital infrastructure, the UK has hindered its ability to embrace new technologies that could enhance productivity and create good work opportunities. Addressing these barriers is crucial to revitalising the UK economy and ensuring that technological transformation benefits workers across all regions.

Fig 1: GDP per hour worked in the UK, compared to historical productivity trends.

The Impact of Automation Technologies

Technological advancements have historically led to significant changes in labor markets. The current wave, driven by automation technologies like robotics and AI, is no different. These technologies necessitate transitions for workers, either in their roles or jobs, and may require new skills and training.

Companies can facilitate smooth transitions by ensuring a good working environment and providing training opportunities, benefiting both the company and its workers.

Robotics have been widely applied in manufacturing, primarily handling goods and facilitating manual work. While they may replace certain tasks, they also bring productivity gains and can create complementary jobs.

Fig 2: Skill demands and wellbeing indicators (placeholder). Data: Gender pay gap in wages (link)

Flexible working arrangements, such as remote work and flexible hours, have become more popular and are associated with higher worker wellbeing.

The Disruption Index and the UK's Innovation Ecosystem

The UK is at a critical juncture in the structural transformation of its economy and in building a world-leading, responsible, and thriving innovation ecosystem. This transformation is already having profound societal impacts, not only on access to work but also on the nature, conditions, and quality of this work.

The opportunities people have to lead fulfilling working lives are fundamentally intertwined with the ways in which innovation systems are designed and support the fulfillment of individual, firm, and regional-level capabilities. These capabilities are conceptually distinct but related and, together, shape the wellbeing and prospects of people and communities across the country.

The Disruption Index provides the first panoramic overview of the scale and trajectories of technological transformation and offers a deeper understanding of the innovation ecosystem beneath headline national statistics. This approach enables exploration of the likely drivers and trajectories of transformation, helping policymakers to identify regional bottlenecks and strengths, and to access the most impactful points for policy intervention.

Regional Inequalities and Technological Transformation

The Disruption Index demonstrates significant regional concentration of technological transformation, reflecting a broader tendency of AI and other automation technologies to concentrate at firm and macroeconomic levels. Regional differences in technological transformation are stark and accelerating, and appear to be scaling along various dimensions of the index, including venture capital investments, R&D expenditure, and the creation of patented technology.

These huge variations, which are moving in similar directions, tend to be missed in national statistics. The established narrative of growing polarization between adopters and laggards at a firm level is therefore borne out across multiple domains at a regional level.

Given the existing deep regional inequalities in the UK, the Disruption Index highlights the growing role that technology and innovation have—and could have in the future—in either exacerbating or reversing current trajectories. Our analysis suggests that there is a risk of further concentration of regional inequalities and that we are at an inflection point in shaping and governing regional innovation ecosystems as well as our national ecosystem.

Technological Transformation and Good Work

Everyday transformation of the economy is led by firms as they make choices to design, develop, and deploy new technology, and to change work as a result. This shapes the creation of new jobs, their nature, and the distribution and access to good work.

These technology adoption choices are related to wider conditions. The distribution of skills shapes firm adoption practices, as well as being an outcome of them. Firms in areas with weaker human capital investment and outcomes have been shown to make adoption choices that could exacerbate regional inequality—deploying new tools in ways that reduce demand for skills and the quality of work—as well as being more likely to eliminate positions overall.

Our analysis suggests that a sharper focus on creating, sustaining, and improving pathways to good work within regional innovation ecosystems is key in shaping better outcomes. In particular, creating opportunities for people to learn new skills, develop their capabilities, and exercise their agency to innovate is required—whatever their role in the innovation ecosystem.

The Rise of Artificial Intelligence

AI has the potential to influence work at all levels except for the most complex managerial decisions. Its applications are still emerging, and while there's much hype, its widespread use is limited but growing.

Traditional AI carries out commands based on data, but generative AI, which can make decisions and analyse data and language, poses new challenges and opportunities. It may impact professional jobs like paralegals, civil servants, and programmers.

There's a need to prepare for AI's integration into the workforce, including rethinking recruitment and training practices to adapt to changing skill requirements.

Productivity and Economic Growth

While automation technologies have the potential to boost productivity, the extent of their impact remains uncertain. Robotics have increased productivity in manufacturing, but AI's influence on overall productivity statistics is less clear.

Quality of services and reduction of errors may improve with AI, similar to the impact of early digital technologies like computers. However, measuring these improvements in traditional GDP metrics is challenging.

A focus solely on GDP growth may overlook significant benefits brought by AI, especially those related to wellbeing and quality enhancements.

Skills for the Future

The demand for certain skills is changing. Employers still highly value "soft" skills like communication, confidence, and customer service. While technical skills are important, especially in IT, the majority of employers are seeking employees adept in interpersonal interactions.

Training and education need to adapt to these changing demands. Both technical and soft skills are essential, and there should be a balance in education and training programs to prepare workers for future roles.

The question is not whether there will be enough jobs, but what skills will be needed to work effectively in the age of AI.

Fig 1: Employment trends in various sectors (placeholder). Data: Employed population by economic sector (link)

Workers face uncertainties about the future and the best approaches to work. Surveys indicate that losing a job is one of the most distressing life events, but being at work can also cause stress and dissatisfaction.

Wellbeing at Work

Workers express that better communication with managers, transparency, social relations at work, time flexibility, and autonomy improve their wellbeing. Financial compensation often ranks lower than these factors.

Recent automation technologies seem to be increasing anxieties among workers, partly due to fear of job loss and changes in work dynamics.

Employers and governments should care about worker wellbeing, as it is linked to productivity and overall societal benefits.

Fig 2: Skill demands and wellbeing indicators (placeholder). Data: Gender pay gap in wages (link)

Flexible working arrangements, such as remote work and flexible hours, have become more popular and are associated with higher worker wellbeing.

Workplace Wellness Programs Can Generate Savings

Amid soaring health spending, there is growing interest in workplace disease prevention and wellness programs to improve health and lower costs.

In a critical meta-analysis of the literature on costs and savings associated with such programs, we found that medical costs fall by about $3.27 for every dollar spent on wellness programs and that absenteeism costs fall by about $2.73 for every dollar spent.

Although further exploration of the mechanisms at work and broader applicability of the findings is needed, this return on investment suggests that the wider adoption of such programs could prove beneficial for budgets and productivity as well as health outcomes.

Fig 6: Wokplace wellness pogammes. Data: Gender pay gap in wages (Wokplace welless pogammes meta analyssis)

The Role of Policy and Employers

Both governments and employers have crucial roles in shaping the future of work in the age of AI. Governments should implement policies that improve citizens' wellbeing, not just focus on GDP growth.

Employers can enhance productivity by improving worker wellbeing, offering training opportunities, and creating supportive work environments. Companies that invest in their employees often find it easier to adopt new technologies and remain competitive.

Social support systems and labor market institutions need to adapt to help workers transition smoothly in a rapidly changing technological landscape.

Adapting Education and Training

Education systems need to evolve to prepare workers for the future. Emphasis on lifelong learning and reskilling is essential to keep pace with technological advancements.

There's a need for broader curricula that combine technical proficiency with soft skills. Early specialization may not be the best approach in an environment where adaptability is key.

Governments and educational institutions should collaborate with industries to ensure training programs align with the skills demanded in the workforce.

Policy Implications for the Future of Work

Building regional responsible innovation ecosystems at a combined authority level with delegated power and resources to shape the ecosystem in a context-sensitive way should be a cross-departmental priority. This could be supported by a network of research and innovation centers across the country, spearheading a socio-technical approach and new knowledge pipelines between the regions and national government.

Industrial strategy should incorporate planning for the technological transitions of all sectors and regions, with national and regional future of work growth strategies. Focusing exclusively on 'ICT' and digital technologies and technology-intensive sectors will likely miss different sorts of opportunities, transitions, and choices where all sectors are being exposed to new technologies.

A cross-cutting mission and sharper focus on creating and sustaining good work—in particular human skills and capabilities and firm-level capacities, especially when developing and adopting new technologies across the innovation ecosystem—should help mediate better outcomes through technological transformation. These better outcomes include the creation of new, good jobs, better work quality, and improved wellbeing.

Be part of the conversation and share your views

We are gathering public insights to contribute to the Pissarides Review into the Future of Work and Wellbeing. Share your opinions and engage in a collaborative discussion using the tool below.

Your views will help shape the findings and recommendations for this review.

Conclusion

Automation technologies based on AI can improve the quality of work, productivity, and worker wellbeing if applied responsibly. Both government and companies have roles to play in ensuring that these technologies are developed and used in ways that benefit society as a whole.

Workers will need to adapt by acquiring new skills, and employers should facilitate this through training and supportive work environments. Balancing productivity gains with worker wellbeing is essential for sustainable growth.

Acknowledgements

This is a project made by Oliver Nash, Anna Thomas, Abby Gilbert, Kester Brewin, and Sir Christopher Pissarides as part of the Pissarides Review into the Future of Work and Wellbeing, which has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation.